Haiku Walking

"HAIKU WALKING"

by Norrie Bissell

When You Go Out

by Norrie Bissell

When you go out into the world

try to use all your senses

touch and taste wild thyme

smell hawthorn and kelp

watch herring gulls soar

listen to the sound of the sea

above all open your mind

and who knows what you will find.

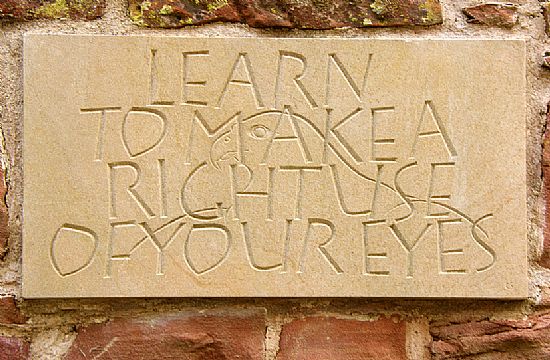

When I wrote that poem I was unaware of the Hugh Miller maxims: “Life itself is a school, and nature always a fresh study.” And “Learn to make a right use of your eyes.” His first publication at the age of 27 when he was working as a stonemason was Poems, written in the leisure hours of a Journeyman and in his subsequent prose writings there is a strong poetic element.

Because of his enquiring spirit he saw no separation between arts and science and wrote passionately and with clarity for his readers. His emphasis on life, nature, enquiry and close observation, in his case through his geological outgoing and study, indicates an approach to the world and to living in it which has much in common with geopoetics.

"Geopoetics is concerned, fundamentally, with a relationship to the earth and with the opening of a world.” Kenneth White, Geopoetics: place, culture, world. The richest poetics come from contact with the earth, from an attempt to read the lines of the world. By developing a heightened awareness of the earth or cosmos, and our relationship to it, we can nourish our creative expression in many different ways and live healthier lives.

To be truly creative I think we need to adopt this approach of sensitive awareness and openness to the world, and work at it regularly and consciously in our various fields of endeavour whether in music, writing, visual arts or sciences or in combinations of all the arts, thinking and sciences. Geopoetics tries to overcome artificial boundaries between disciplines of knowledge and unify them. This sits well with the approach of Hugh Miller who rejected the view that there was an arts and science divide in life.

Having undertaken some initial research, if we go out with our senses attuned and our minds open we can come back with some notes and short poems and images as food for our creative imagination. This is sometimes called haiku walking.

You can find evidence of this approach in a number of writers and thinkers who have laid the groundwork for geopoetics. The American naturalist and writer Henry Thoreau and the Scots polymath Patrick Geddes are two examples along with Thomas Muir and, in some respects, Hugh Miller. They could be called ‘outgoers’ or ‘intellectual nomads’ since their work was based on going out into the natural world of which we are a part and responding creatively to it in a variety of ways. As an aside, I was interested to learn that John Muir named a glacier in Alaska after Miller.

Here are some examples of Miller’s vivid style of writing:

"The moon, at full, had just risen, but there was a silvery mist sleeping on the lower grounds that obscured the light, and the dell in all its extent was so overcharged by the vapour, that it seemed an immense overflooded river winding through the landscape. Donald had reached its further edge, and could hear the rush of the stream from the deep obscurity of the abyss below, when there rose from the opposite side a strain of the most delightful music he had ever heard. He stood and listened: the words of a song of such simple beauty, that they seemed, without effort on his part, to stamp themselves on his memory, came wafted on the music, and the chorus, in which a tiny thousand voices seemed to join, was a familiar address to himself. 'He! Donald Calder! ho! Donald Calder!'"

Scenes and Legends of the North of Scotland, p443.

"The Cleopatra, as she swept past the town of Cromarty, was greeted with three cheers by crowds of the inhabitants, and the emigrants returned the salute, but, mingled with the dash of the waves and the murmurs of the breeze, their faint huzzas seemed rather sounds of wailing and lamentation, than of a congratulatory farewell."

Inverness Courier, 22nd June 1831

republished in A Noble Smuggler and Other Stories, p44

Miller revealed himself as also an environmentalist, arguing successfully against the proposed carriage drive through the Meadows in 1855, and proclaiming "the right to roam" in such articles as Glen Tilt Tabooed.

Of course, there are major differences between geopoetics and Miller. He was a man of his time and a major religious figure, whereas geopoetics is deeply critical of Western thinking and practice over the last 2500 years and its separation of mind and body and of human beings from the rest of the natural world. It proposes instead that the universe is a potentially integral whole, and that the various domains into which knowledge has been separated can be unified by a poetics i.e. a world outlook which places the Earth at the centre of experience. But Miller’s achievements in geology are well established and geology is a fundamental element of geopoetics.

I’ve only been able to skim the surface of this subject here, but it seems to me that there is much more could be done to develop this analysis further. The Isle of Luing Community Trust, of which I’m Vice-Chairman, intends to develop a geology trail into the slate quarries in Cullipool on Luing where I live, and it could be that there would be room for further collaboration related to this and other projects.